VISIT TO SENEGAL

June 1st to 5th,

2012

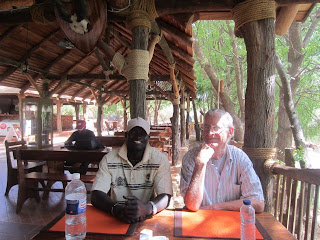

We hired Lamin Gaye as our

driver. He has taken other VSO

volunteers to Senegal and

speaks Woloof, one of the local languages common in The Gambia and Senegal. His

car is big and sturdy.

The road trip to/from was quite

rough. A lot of the road is in poor condition. Lamin was skilled at

spotting the many hazards and taking evasive action to protect his car and

passengers.

We started early from Brikama

in order to catch the first ferry at 7:00 a.m.

Lamin had transferred the car to the north bank at Barra the night

before. Otherwise, we would have had to wait many hours for a space for the car

on the ferry. The Banjul/Barra ferry is

unbelievably slow. If it were any slower, it wouldn’t be moving at all. Only

one of the four engines functions. Getting on and off is truly an experience,

all the crowding and shoving. Watch for pick pockets!

Another aspect of our trip to Dakar: We went eight

hours without the use of a bathroom. Somehow, the body adapts. It

was so hot (the car has no air-conditioning.) We had to watch our fluid

intake to avoid dehydration.

It took Lamin an hour at the border to deal with his papers, associated with

taking an automobile into Senegal.

Meanwhile, we, waiting in the car, were under siege, as you can only imagine,

with little urchins wanting money or to sell us nuts, fruit, cakes, water. Our

formalities were also like nothing we have seen at any other border.

First we went to the Gambian police, who copied all of our passport information

into a big bound ledger book with many columns. Then we went to the Gambian

immigration police who did the same in another set of books. Each added stamps

to our passports. I can't imagine what use those books would ever have?

But there they are. And once the books are full, what happens to them? If

any one wanted to know about our crossing the border, what would they do?

How would they find the information unless they already knew when and where we

crossed? On the Senegal

side, they also keep a book and write everything, row by row. But Senegal is more

streamlined. They only have one book and one police.

The ride to Dakar

is through flat, dry, desert-like countryside dotted with small villages. Closer to Dakar, we passed salt production flats. We arrived late afternoon. Dakar

reminded me of Buenos Aires

in one respect. There are some modern, impressive buildings and workers

in suits and ties. There are also people living on the street, as in Argentina.

From our hotel window, we saw, each night, directly across from the hotel, a

family set up pieces of cardboard, supported by benches and stools, and spread

out thin mattresses and blankets for the night. That's where they live.

In the morning, they got their kids up, made breakfast, and put all the pieces

away again. Up and down the street others were sleeping on the sidewalk.

The hustlers (bumsters) were very thick. Somehow, they knew to speak

English to us. Same stories, same strategies, very persistent. We felt

like glue paper, and they were the flies. Coming back from a performance,

it was more than hustlers. They had their hands on me and had my bag open, but

didn't get anything. It started as an offer, so friendly, to sell a

shirt, but the shirt was like the newspaper used by the gypsy children in Rome. I knew to be

vigilant (grab my wallet before they did) and with Ilana's help, we managed to

escape the situation. Shopping in the market is a difficult experience. The sellers in the street or shops come over

to you and do not leave you alone. They

are very persistent and stubbornly unwilling to hear no.

We visited Dakar

at an auspicious time. The Biennial Arts Festival was underway. There was

so much to do and so much to see. We went to many galleries and saw the work of

many artists. We were fortunate that the National Ballet of Senegal was

performing on June 2nd at Dakar's

Institute Français. The Institute is like Alliance Française in the Kombos,

The Gambia but much bigger. It is a very nice place, with a lovely restaurant,

exhibition spaces and outdoor performance space. It was a short walk from our hotel. We went

there for dinner - it has s a wonderful French restaurant, and then the show.

'Ballet' may be a bit misleading. This is modern dance with a strong West

African orientation. (When we see an ad for this company’s tour in the US, we will

surely go again.) It was excellent. The dancers were very well trained

and the production was exciting: The drumming, the costumes, the dancing, the

singing, acrobatics, and clowning (One fellow seemed to mimic Arlecchino of the

Commedia dell’Arte). It was so rich, affecting all senses at once and difficult

to absorb it all. We had not had a chance to witness much artistic life in The

Gambia during our short stay here. We are so glad we went to Senegal and were able to find a bit of what is

happening in West Africa. Senegal seems to be a source for innovation in

the arts that is constantly carrying over and influencing culture in the US,

particularly for the African American community.

The Artists’ Village is a government institution that provides living space,

studio facilities, and an exhibition space for Senegalese artists. While

in the gallery, we connected with an Italian economist, who dabbles with

abstract art. He had a couple of pieces in the show. He took us around to

introduce us to some of the Village’s artists. Most speak English and exhibit

in the US.

When needed, however, he provided translation because he speaks Italian,

English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and some Arabic. Ilana bought a simple,

small painting from one of the artists we met.

The Ille Gorée is the original European (Dutch were the first) outpost. The ferry

to the island was relatively new, fast and comfortable with enough seats for

everyone. We waited for the ferry at a

modern ferry building with seats and an orderly queue, all so unlike the ferry

passage in Banjul. There is slave house on the island, which

most tourists visit. In reality not many slaves passed through the island. We

eschewed a guide and decided to wander around the island on our own. There are

small, curvy streets, where the buildings are painted with pastel colors, like

in Italy.

There are colorful, blooming, climbing, and potted plants. The buildings are ancient. Some are

collapsing. Many need repairs. A few have been restored. Views of the

water surrounding the island appear here and there through some passageways,

windows or garden plots.

We found some artists in their

studios and conversed with them. While walking up the path up to the castle, we

met a Haitian American woman. (There are no vehicles on the island. It is

therefore completely pedestrian friendly.) We started talking. (Her

name is Fania Simon.) She told us that she is a writer. She came to Senegal for a

visit and ended up living with a family in a compound on the island at the very

top, in the ruins of the castle. She has been on her extended visit for

two years now. She has published 20 books. She gave us one of her

books of poetry. We walked up to the compound and stayed as long as we could

and still make it back to the mainland on the ferry. Here is an African

American who has lived in Senegal

for two years on this historic island. Well, she has learned a lot and we

were very curious to hear what she had to say. We talked a lot about the

status of women in Senegal

(very bad, she said) and exploitation of children (shocking - think Oliver

Twist and worse.) In a way it was a tour of Dakar from a social and economic stand point.

We talked about massive levels of injustice and the complexities of even

understanding it, certainly not knowing how to deal with it.

(Below is a Google English translation from French of information about the

exploitation of children in Senegal.

(

www.actionsenegal.be) Fania (the

woman we met), gave us a hard copy of the booklet referred to in the material

below. (I have included this information in case you want to learn more. It is

at the end so take as much as you want.)

With our last ounce of energy we went to Marché des HLM fabric market. This

market probably has more fabrics and artisans that all of what exists in The

Gambia combined. I said to myself, I can't believe I am here experiencing this.

It was such a jumble and crush of humanity, sewing machines whirring, and

stacks of endless amounts of batiks, and fabrics with enthusiastic sellers

promising great (the best) prices. I am not sure we did so well on the

price. We were too worn out to do battle.

We bought a piece of Moroccan jewelry from a Moroccan shop near the hotel that

is referred to as the street of the Moroccans. I offered half the quoted

price. They accepted immediately. I should have offered one third, as

I have previously. You offer one third and then go up a bit. They

accepted half, saying it was Friday. Even at half, the cost was a fraction of

what one would pay in the US.

So we paid a bit more. It is a nice piece, which is the most important in

the long run.

The Lac Rose (the Pink Lake,) is where workers from Guinea Bissau and Mali mine salt from the bottom of the lake

(Senegalese don't do the work, it is too hard. The foreigners do it -

they are migrant labor and get the toughest work and are paid the least.)

The lake is pink, hence the name. The men go by canoes to the shallowest parts

of the lake and, standing in the water, hack the salt from the bottom and load

it onto the canoe. When the canoe is

full, they pole it to shore. The women carry the salt on their heads in buckets

and dump it on large piles sorted by the quality of the salt. Some of the salt is of high quality, purely

pinkish, white, and is sold directly to buyers. The poor quality salt is sold

to a factory nearby for processing. We hired a boat and crossed the lake to get

a close look at the process. Afterwards we had a lunch at an outdoor restaurant

over looking the pink lake. It was so scenic, romantic, and peaceful.

Lamin, our driver lost the way

on the way to the lake. There is so much construction going on in Senegal that the

roads and the scene are constantly changing, so he became disoriented. He

speaks Woloof, so he was able to ask directions, but many don't know their way

themselves, so the information can be very wrong. We did arrive, but on

the way, saw a behind the scenes look at the emergence of new neighborhoods.

All of this was interesting to our eyes, coming from The Gambia where the

situation is not the same. Around Dakar we saw many modern

apartment buildings, while other apartments are in the process of being

constructed. This means that the country

is also developing modern infrastructure and utilities for those apartments

(electricity, water, sewage,) while in The Gambia we tend to see construction

of more traditional compounds, often with less amenities.

On the way back to The Gambia, we spent a half a half day at the Bandia Nature

Reserve. This is a safari park. We rode on a vehicle built for viewing animals

and had a guide. The cost is a bit stiff, but it is worth it if you like to see

animals in their habitat, up close. We saw giraffes, impalas, antelopes,

wart hogs, crocodiles, hyenas, zebras, buffalo, many monkeys, many birds, and

others I am not remembering. The rhinos didn't show themselves.

They are the highlight. We saw plenty of their excrement, but not the

individuals who left it.

The ferry ride back to Banjul was very difficult

because all but one of the ferries were broken down. The one that showed

up had only one engine running. It took a long time for the ferry to arrive and

of course all the waiting multitude were anxious to board before the gate

closed, though no one seems to pay much attention to capacity limits, life

preservers, or life boats. One trusts to ones fate, I guess. We sat next to a

member of the Ministry of Agriculture (NARI, in fact) who is a soil

surveyor. He studied at the University

of Illinois. Since

the crossing took so long, I received a thorough briefing on Gambian soils,

problems in agricultural development here, and certain other issues relating to

NARI. He works at Yundum, which is 10 km from Brikama. It is NARI's

western station, a counterpart to Sapu in the east. His driver and Lamin were

both stranded in Barra on the northern side of the river. They had to sleep

overnight to wait to bring their vehicles back to Banjul some time the next day.

Attachment: About Action Senegal projects related to

exploited children (online translation of brochure in French)

In recent years, the Action Senegal Association has been active in the bush and

in the Sahel in Senegal for partnership projects, funding, among other initiatives,

in consultation with local authorities: Building wells, plantations, classrooms

, clinics ... It is through these

actions in the bush, talking with the local residents, I discovered the problem

of children in care of marabouts of Senegal

who are false. True marabouts, teach talibé children attending religious

classes in real Koranic schools subsidized by the state. But false marabouts enslave

children in daaras that are illegal. The

lives of these enslaved children of false marabouts ('martyrs') caught my

attention and curiosity. Wanting

to check carefully all the information received from people in the bush, I walked

through the doors of illegal daaras to see what was really happening and I

discovered the horror. With the

help of an educator on a mission to Senegal,

we began a census of the number of illegal daaras in the slums of St. Louis, the number of children in each marabout’s daara,

in each region of Senegal.

I realized that the problem was very serious because it concerns tens of

thousands of children. Shocked to

have seen children abused and whipped, on my return I talked to friends and journalists.

Television Walloon Picardy

"Notélé" went onsite and directed his first documentary "The

white tornado in Black Africa". Then

two other reports were made: "In

the heat of a village in the Sahel" and

"descent into hell of talibés". Following the reports of Notélé,

we found we could educate those around us.

We wanted to act in three phases.

1st Phase:

An ambitious project: building a shelter for 13,000 children from marabouts’

daaras and children in difficult circumstances of Sor Pikine (St Louis).

This

facility opened November 6, 2009.

Every

day, many children, aged 3-15 years attended. A team of volunteers are working

in Senegal (Institutrices - doctor - health care assistant - responsible for

carpentry / sewing / craft ...) The children learn to read, compute, and to

play too, as do many other children in the world.

They are fed, they can rest, sleep

safely!

The oldest are just

starting their professional training.

Without this place, a home, these children are in the street, begging all

day and even at night, for an alleged 'marabout', a disbeliever unworthy to

bear that respected and respectable title.

These

children spend all their youth to be talibés martyrs!

This shameful reality we opposed!

These false marabouts exploit

gullibility and family poverty. They make them believe that their children will

be properly educated in the big city so they can acquire work that will ensure

their future and that of their families in the village.

But the reality is different: In miserable

daaras, without any comfort or hygiene, they are obliged to recite the Koran

for hours in a language they do not understand, then walk the sidewalks,

begging for the sole benefit of these so-called 'marabouts' and cronies.

The child who does not return enough

money to feed their greed is beaten, tortured, starved, and chained like the

slave he has become. During the trips, we often met the real marabouts, anxious

to provide a good religious and general education for their students, within

respectable Koranic schools. Confusion between true Islamic schools and illegal

daaras is common. Many political, religious, and social groups with whom we

have shared our outrage are in support of our cause.

Thus, very quickly awareness of the

urgent need to denounce these atrocities on these (very!) young, defenseless

children has become widespread! Awareness of the plight that enslaved talibés children

who live every day and every night that goes by in misery is our priority. No

one can say: “I did not know.” Warn ignorant families, inform young people themselves

through education in schools educate and empower all responsible authorities

(both religious and political) are all goals that we want to achieve.

2nd Phase:

Production of books and Kamishibaïs by Daniel Barbez for advocacy

work in the bush

Daniel Barbez created a portable communications tool: the Kamishibaï

(Japanese theater) to educate the illiterate population in the bush against

sending children to marabouts in major cities. He explains that it is possible

to study religion and vocational training not far from home. He warns that

there are false and true marabouts.

3rd phase

Publish a book of photos and a DVD. It seemed most appropriate to introduce

this hard reality not always easy to confront by publishing a book. The book

documents through research the correlation between items in the Declarations of

the Rights of the Child, the verses of the Koran, and the Code Noir of Louis

XIV on slavery.

(

July 31, 1990, under the

administration of President Abdou Diouf, Senegal ratified, like many countries

in the world, the Declaration of Rights of the Child (DDE). This text was

presented by the United Nations in November 1959. A second text followed: the

International Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1989 .)

I certify that all the pictures in the book are authentic: They are real and

not fake; they were taken in Senegal

during visits to daaras and centers for child talibés.

By the widest dissemination of these

photos to religious and political leaders, we believe that the creation of

effective laws may regulate the establishment and operation of these daaras,

infamous for the sole benefit of greedy miscreants who hide under the false

name of 'marabout'.

Hence we

provide the Koran readings and references to various verses.

I actually read the 600 pages of the

Koran to make reference in the book to some verses which clearly show that the

Muslim religion does not tolerate this kind of practice to these young

children.

A second priority is to

legally stop the influx of children from neighboring countries and bush

villages.

Then, with the support

and vigilance of everyone, including local religious authorities, it is

possible to establish effective supervision in neighborhoods to remove

permanently the reality of talibés martyrs.

Finally,

the establishment of legitimate schools is the most direct route to the

harmonious education of these children.

You can find this book 'Child talibés, child slaves'. If each of you to

discover ten other people, which in turn will introduce to another ten, which

in turn ...

Then, one day, the child

talibés can, thanks to you, break their chains!

And live free, like all children of

the world.

ooo The views are my own ooo